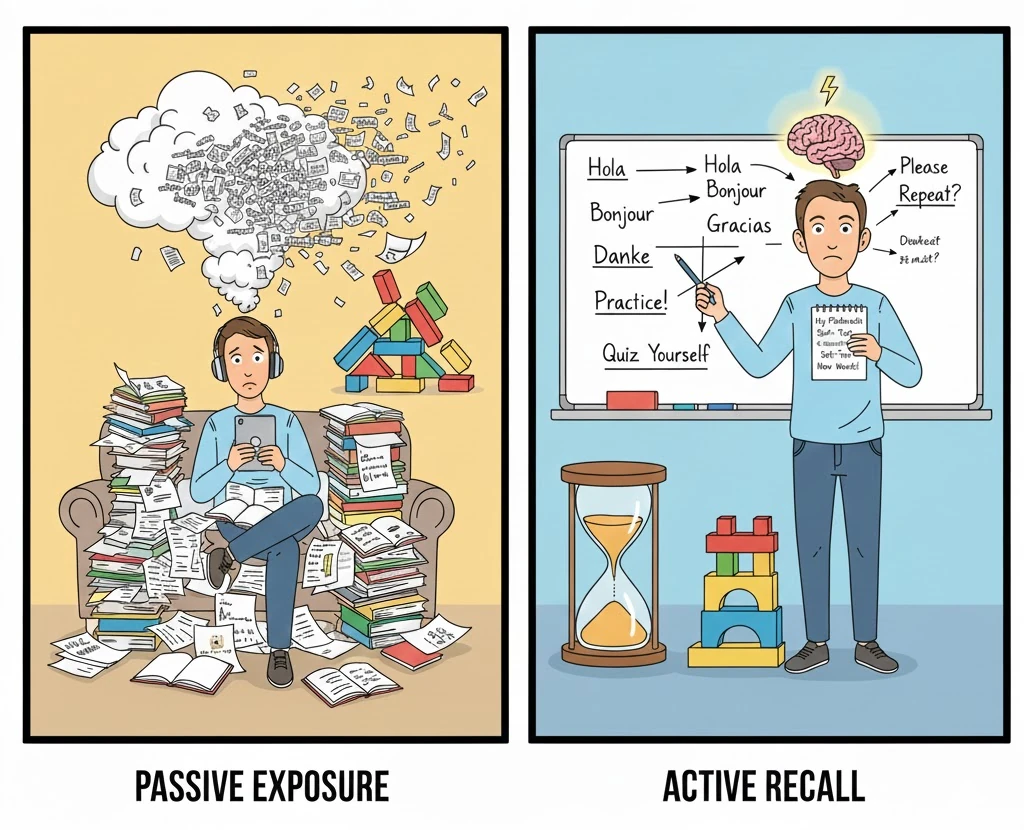

Many language learners rely heavily on passive exposure—reading articles, listening to podcasts, or watching movies in the target language—hoping that repeated exposure will eventually “sink in.” While passive activities can complement learning, science shows they are often insufficient for real mastery. To lock a language into long-term memory, you need more than just exposure—you need to actively engage your brain. That’s where active recall comes in.

In this post, we explore why passive exposure frequently falls short, how active recall changes the game, and practical ways to use active recall (often in combination with spaced repetition) to master vocabulary, grammar, and more.

What’s the difference between passive exposure and active recall?

- Passive exposure (or passive review): you read, listen, or watch language material without forcing yourself to retrieve or produce the information. For example: reading a text, listening to a podcast, watching a film. (Wikipedia)

- Active recall (a.k.a. retrieval practice): you actively test yourself—trying to remember words, grammar rules, meanings, or sentence structures WITHOUT looking at the answer. For example: flashcards, self‑quizzes, writing from memory. (Birmingham City University)

Passive exposure is easy and feels productive, but research shows that active recall produces much stronger, longer‑lasting memory.

Why active recall is so powerful

• The “Testing Effect”: retrieving strengthens memory more than re‑reading

One of the most robust findings in cognitive psychology is the testing effect. The act of recalling information improves long-term retention more than restudying or re-reading. In vocabulary learning experiments, learners who actively recalled (versus those who only re-read) consistently outperformed on later tests. (PMC)

• Active recall + spaced repetition = long-term memory, not just short-term gains

Active recall is powerful on its own. But combining it with spaced repetition — revisiting material at optimized intervals — makes memory far more durable. Spaced repetition helps overcome the “forgetting curve,” ensuring that knowledge stays accessible after days, weeks, or months. (ScienceDirect)

• Passive exposure alone often fails to produce stable retention

Studies comparing passive review (e.g., rereading or passive recognition) to active methods find that passive approaches lead to much weaker recall over time.

Moreover, some evidence suggests that even frequent passive exposure (reading or listening repeatedly) does not significantly boost recall performance unless combined with retrieval/practice tasks. (ERIC)

• Active recall reveals gaps and strengthens retrieval pathways

When you test yourself, you quickly discover which words, patterns, or grammar you don’t yet know. This feedback loop helps you focus effort where it’s most needed and strengthens the neural pathways required for active use (speaking, writing), not just passive recognition. (Osmosis)

What This Means for Language Learners and for Aprelendo Users

If you rely only on passive exposure (reading articles, listening to dialogues, watching videos) you may gain comfort with the “sound” and rhythm of the language. But chances are, a lot of that material will remain at the level of recognition, not active use.

In contrast, by combining active recall (e.g., flashcards, self‑quizzes, writing from memory)—especially with spaced repetition—you give your brain repeated opportunities to retrieve and produce what you’ve learned. That builds stronger, more accessible memory traces.

For users of Aprelendo, the goal should be to use features that enable active engagement—like the Study section—not only reading or passive listening, but forcing yourself to recall, produce, and reflect.

Practical Ways to Use Active Recall in Your Language Learning

Here are some actionable strategies:

- Use flashcards (with spaced repetition): Instead of only reading vocabulary in context, use flashcards that force you to recall—translation, meaning, example sentence.

- Write from memory: After reading a text or listening to a conversation, close your materials and try to write or summarize what you remember.

- Self‑quizzes & tests: Periodically quiz yourself on vocabulary, grammar rules, or sentence formation instead of just re‑reading.

- Active listening with response: When listening to audio content, pause and try to summarize or explain what you heard—without looking.

- Mix input and output: Combine passive exposure (reading, listening) with output tasks (writing, speaking, recalling) to reinforce retrieval.

For maximum benefit: combine these techniques with spaced intervals — revisit material after a day, then after a few days, then after a week, etc.

When Passive Exposure Can Still Help

Passive exposure has value: it increases familiarity with rhythm, intonation, natural usage, and context. For example, reading novels or watching shows can build intuition for grammar patterns, tone, and style.

Recent research even suggests passive exposure may support learning by providing a foundation (e.g., exposure to many examples) that can later be consolidated through active techniques. (OregonNews)

But passive exposure alone almost never leads to reliable long-term recall or active use—especially when it comes to vocabulary production, grammar application, or speaking/writing proficiency.

Therefore: treat passive exposure as a complement, not a substitute. The backbone of your learning should be retrieval-based, active practice.

Leave a Reply